Multi-Path TCP: revolutionizing connectivity, one path at a time

The Internet is designed to provide multiple paths between two endpoints. Attempts to exploit multi-path opportunities are almost as old as the Internet, culminating in RFCs documenting some of the challenges. Still, today, virtually all end-to-end communication uses only one available path at a time. Why? It turns out that in multi-path setups, even the smallest differences between paths can harm the connection quality due to packet reordering and other issues. As a result, Internet devices usually use a single path and let the routers handle the path selection.

There is another way. Enter Multi-Path TCP (MPTCP), which exploits the presence of multiple interfaces on a device, such as a mobile phone that has both Wi-Fi and cellular antennas, to achieve multi-path connectivity.

MPTCP has had a long history — see the Wikipedia article and the spec (RFC 8684) for details. It's a major extension to the TCP protocol, and historically most of the TCP changes failed to gain traction. However, MPTCP is supposed to be mostly an operating system feature, making it easy to enable. Applications should only need minor code changes to support it.

There is a caveat, however: MPTCP is still fairly immature, and while it can use multiple paths, giving it superpowers over regular TCP, it's not always strictly better than it. Whether MPTCP should be used over TCP is really a case-by-case basis.

In this blog post we show how to set up MPTCP to find out.

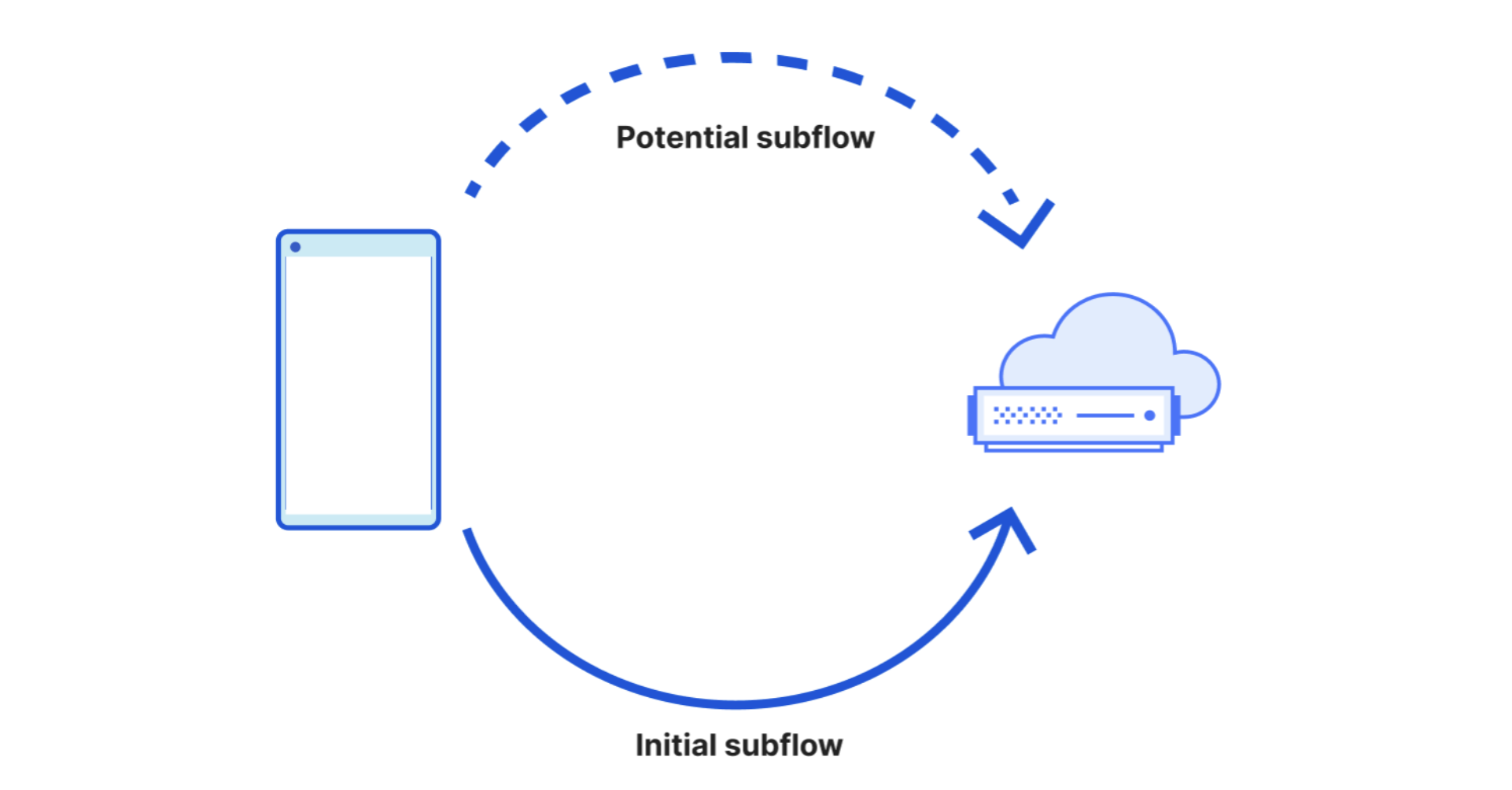

Internally, MPTCP extends TCP by introducing "subflows". When everything is working, a single TCP connection can be backed by multiple MPTCP subflows, each using different paths. This is a big deal - a single TCP byte stream is now no longer identified by a single 5-tuple. On Linux you can see the subflows with ss -M, like:

marek$ ss -tMn dport = :443 | cat

tcp ESTAB 0 0 192.168.2.143%enx2800af081bee:57756 104.28.152.1:443

tcp ESTAB 0 0 192.168.1.149%wlp0s20f3:44719 104.28.152.1:443

mptcp ESTAB 0 0 192.168.2.143:57756 104.28.152.1:443Here you can see a single MPTCP connection, composed of two underlying TCP flows.

Being able to separate the lifetime of a connection from the lifetime of a flow allows MPTCP to address two problems present in classical TCP: aggregation and mobility.

Aggregation: MPTCP can aggregate the bandwidth of many network interfaces. For example, in a data center scenario, it's common to use interface bonding. A single flow can make use of just one physical interface. MPTCP, by being able to launch many subflows, can expose greater overall bandwidth. I'm personally not convinced if this is a real problem. As we'll learn below, modern Linux has a BLESS-like MPTCP scheduler and macOS stack has the "aggregation" mode, so aggregation should work, but I'm not sure how practical it is. However, there are certainly projects that are trying to do link aggregation using MPTCP.

Mobility: On a customer device, a TCP stream is typically broken if the underlying network interface goes away. This is not an uncommon occurrence — consider a smartphone dropping from Wi-Fi to cellular. MPTCP can fix this — it can create and destroy many subflows over the lifetime of a single connection and survive multiple network changes.

Improving reliability for mobile clients is a big deal. While some software can use QUIC, which also works on Multipath Extensions, a large number of classical services still use TCP. A great example is SSH: it would be very nice if you could walk around with a laptop and keep an SSH session open and switch Wi-Fi networks seamlessly, without breaking the connection.

MPTCP work was initially driven by UCLouvain in Belgium. The first serious adoption was on the iPhone. Apparently, users have a tendency to use Siri while they are walking out of their home. It's very common to lose Wi-Fi connectivity while they are doing this. (source)

Currently, there are only two major MPTCP implementations — Linux kernel support from v5.6, but realistically you need at least kernel v6.1 (MPTCP is not supported on Android yet) and iOS from version 7 / Mac OS X from 10.10.

Typically, Linux is used on the server side, and iOS/macOS as the client. It's possible to get Linux to work as a client-side, but it's not straightforward, as we'll learn soon. Beware — there is plenty of outdated Linux MPTCP documentation. The code has had a bumpy history and at least two different APIs were proposed. See the Linux kernel source for the mainline API and the mptcp.dev website.

Comments (3)

Great introduction! Looking forward to more HTML5 articles.

Thanks Jane! We have more articles coming soon 🚀

This helped me understand semantic tags better. Thanks!

Could you also write about Canvas API in detail?

Leave a Comment